Published 02/03/2021

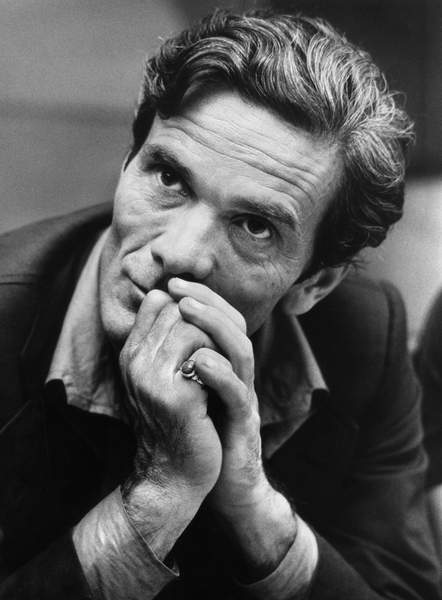

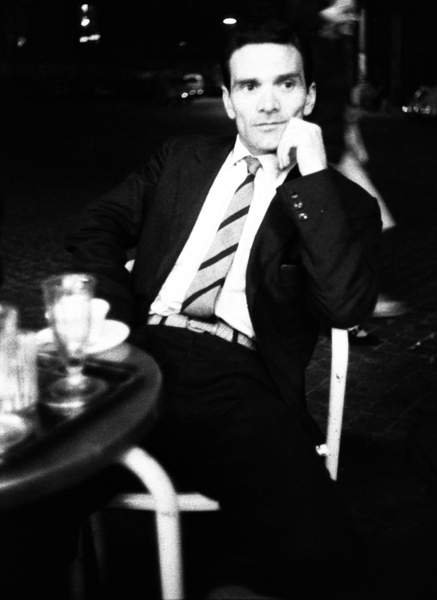

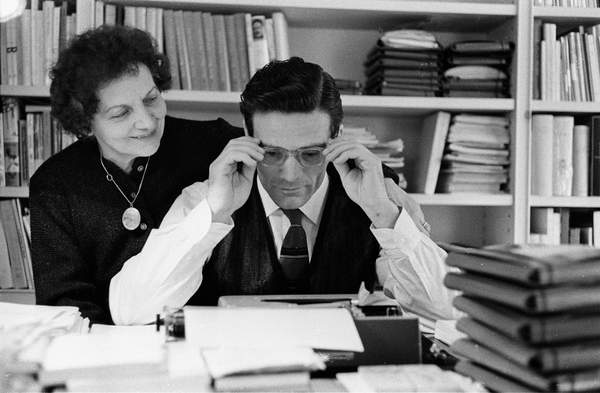

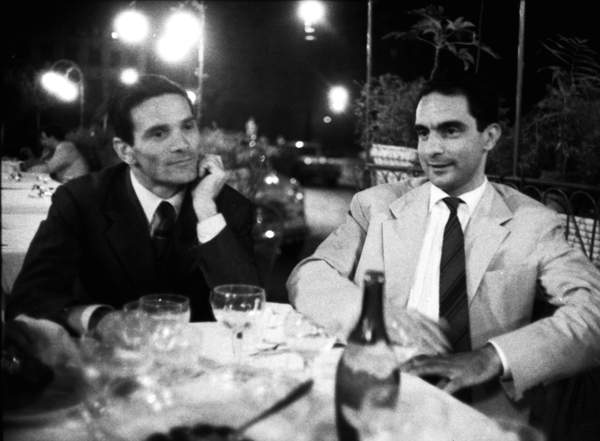

5 March 2022 marks the centenary of Pier Paolo Pasolini's birth. Let's look back at his life.

Pier Paolo Pasolini, born March 5, 1922, in Bologna, Italy, is known today for his novels, poetry, and controversial films. Throughout his career, in both writing and films, Pasolini brought attention to the people often overlooked in Italian society and was not afraid to speak out against the hypocrisies of religion, the government, or the upper classes.

Pasolini faced a great deal of scrutiny and public criticism in his time but he never conceded or compromised, solidifying his legacy.

Pasolini began writing poetry at a young age and went on to study art history and literature at the University of Bologna despite Fascism sweeping the country.

Pasolini began pushing boundaries with his first book of poetry, released in 1942. Poesie a Casarsa, ‘Poems from Casarsa’ was written in his mother’s dialect of Friulian in an early attempt by Pasolini to oppose Fascism in Italy. Benito Mussolini had banned the use of dialects in public in an effort to “unite” Italy with one standard Italian language.

Pasolini resented the lack of freedom to write criticisms and critiques of the Italian petite bourgeoisie, a group he later called “the most ignorant in all of Europe”, in his 1963 film La ricotta. Therefore, he wrote about the working class, the people he associated with.

In 1947 Pasolini joined the Italian Communist Party, and soon became the secretary of the Casarsa branch, although he was later expelled from the group for being gay. Throughout his life, he remained a Marxist and atheist.

1955 brought Pasolini his first acclaim as well as his first major controversy. His novel Ragazzi di vita was inspired by his five years living in postwar Rome. The Rome Pasolini shares is that of the poor, the Rome he would later show visually in his neo-realist films. This novel saw public outcry over its themes and was heavily censored in later editions.

"...writing literature and filmmaking are not mutually opposed. On the contrary, I'd even say they're comparable forms. The desire to express myself through film comes from my need to adopt a new technique- one that would renew me. It also means the desire to break away from obsession. My long-standing passion for films goes back to when I was a boy and was influenced by Chaplin and Dreyer who were a part of my stylistic and ideological world."

It is during this time in Rome that Pasolini began dipping his toes into the film industry by collaborating on scripts with fellow Italian filmmakers. Most notably, Mario Soldati’s La donna del Fiume, ‘The River Girl’; Federico Fellini’s Le Notti di Cabiria, ‘Nights of Cabiria’; Franco Rossi’s Morte di Un Amico, ‘Death of a Friend’; and Mauro Bolognini’s La Notte brava, ‘Bad Girls Don't Cry’ and From a Roman Balcony. These films covered a variety of controversial themes such as prostitution and crime, and as a result, the Italian Committee for the Theatrical Review of the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage censored Death of a Friend, Bad Girls Don't Cry, and From a Roman Balcony.

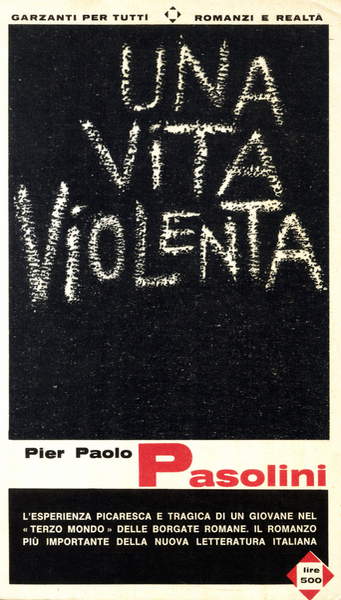

In 1959 he released his novel Una Vita Violenta, ‘A violent life’, which was the basis for his 1961 directorial debut, Accattone. The following year, Una Vita Violenta was again adapted for the screen, co-directed by Paolo Heusch and Brunello Rondi.

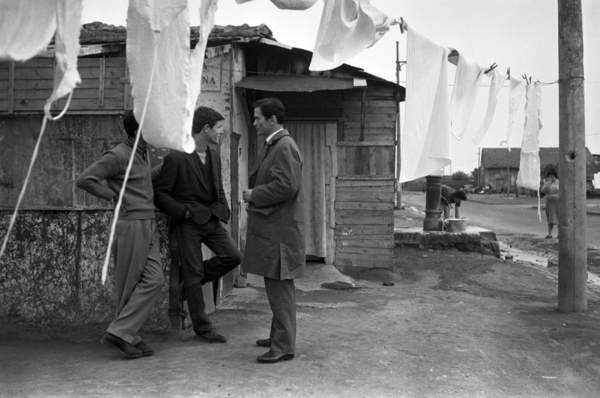

Accattone is considered one of the last of the classic Italian neo-realism films, or the first of a new type of neo-realism that he would carry through some of his most quintessential films. Like other neo-realism films, it was shot on location, depicted the poor or working-class, and used non-professional actors. But Accattone goes beyond that. It presents people living somewhere no tourist would ever dream of visiting, the slums and the underworld on the outskirts of Rome, and the type of people who really live there.

He presented a take on neo-realism that actually depicted the despair and desperation and the beginning of the cultural genocide of the urban sub-proletariat. He captured what classic neo-realism only attempted to depict. Pasolini elaborated on this topic in his article, Il mio Accattone in Tv dopo il genocidio, ‘My Accattone on TV after the genocide’ published in Corriere della Sera in 1975. The articles he wrote for Corriere della Sera were later compiled into the Lettere Luterane.

© Farabola / Bridgeman Images

Accattone was popular among the public because the realism the film portrayed was a new experience for filmgoers. That same sentiment caused mixed reviews among critics who thought the realism was too much. Public interest was aroused when posters advertising the film had a warning that there was no admittance for children under 18, becoming the first Italian film to receive the VM18 rating. Soon after its premiere, the film was pulled from theatres around Italy due to its content.

Pasolini followed up Accattone with his 1962 film Mamma Roma. Much like its predecessor, Mamma Roma is the story of the often-neglected people of Italy and the lengths they would go to survive. Where Accattone follows the thieves and the prostitutes through their life in the slums, Mamma Roma explores the struggle to escape and forget that past in order to attempt assimilation into the petite bourgeoisie class.

Mamma Roma had a complicated relationship with the public and the government. It made its premiere at the 1962 Venice Film Festival but was immediately pulled from the theatre due to obscenity and immorality charges, making it the first film to be shown at the festival that was denounced at the premiere. The charges were eventually dropped and a month later the film was allowed to return to theatres. Mamma Roma did not premiere in the United States until the 1990s.

Mamma Roma was immediately followed up by the short film La ricotta which was Pasolini’s contribution to Ro.Go.Pa.G., a film comprising four short films, each directed by a different director. The other short films included Jean-Luc Godard’s Il Nuovo mondo, Ugo Gregoretti’s Il Pollo ruspante, and Roberto Rossellini’s Illibatezza. La ricotta has Orson Welles in the role of a director, a kind of caricature of Pasolini, directing a film about the crucifixion of Jesus Chirst. It presents criticism over how the Catholic Church turned a blind eye to the blights of Italy’s poorest with a satirical flair.

La Ricotta was confiscated upon its release for “for insulting the religion of the state” and Pasolini was tried and sentenced to several months in prison. That sentence was later suspended.

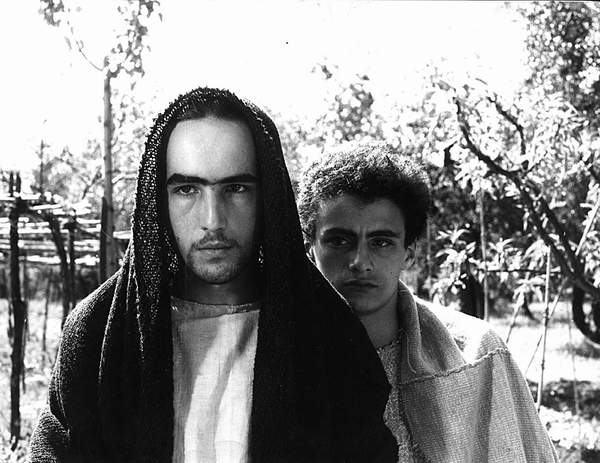

Pasolini’s next film was a less polarizing depiction of a classic religious tale. His 1964 film Il vangelo secondo Matteo, ‘The Gospel According to St. Matthew’ was shot in the neo-realist style, casting ordinary people including his own mother for the role of Mary at the time of the Crucifixion. Additionally, there was no screenplay written for the film, rather the words were taken directly from Matthew.

Despite the film being protested by right-wing groups, it received high praise from the Church and received an award by the International Catholic Film Office for the best religious film of the year. It received the Special Jury Prize at the Venice Festival and was reviewed positively by critics.

Decades later the film was still seen in high regard. In 1995 the Vatican compiled a list of “great films” in honour of the 100th anniversary of cinema. They praised it for “...avoiding the artificiality of most biblical movie epics. Director Pier Paolo Pasolini is completely faithful to the text while employing the visual imagination necessary for his realistic interpretation”

The same year Il Vangelo secondo Matteo was released, Pasolini released a documentary titled Comizi d'amore, ‘Love Meetings’. In this documentary Pasolini ventures around Italy, asking young and old about their thoughts on sex, homosexuality, divorce, sexism, masculinity, and the new brothel laws. It provides a rare glimpse into the psyche of Italy in the 1960s.

With his next film, 1966’s Uccellacci e Uccellini, ‘The Hawks and The Sparrows’, Pasolini began exploring a more fabled and whimsical criticism of Christianity and Marxism. The playfulness of the film made Uccellacci e Uccellini the polar opposite of lI Vangelo secondo Matteo in a stylistic approach, causing confusions among fans of the latter. Although critics enjoyed the film, it was not commercially successful.

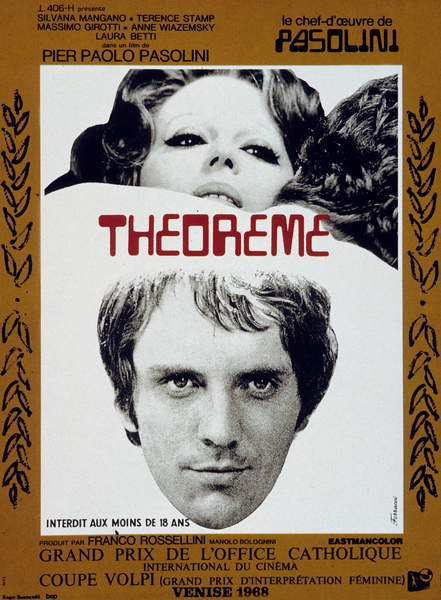

1968 brought the return of controversy with Teorema, ‘Theorem’. The film conveys some Marxist beliefs, but mainly focuses on the isolation and monotony of bourgeoisie life. It is the first of three films that explore the psychology of the bourgeoisie. Some perceive the film as another Christian allegory, as the mysterious, Christ-like figure causes this bourgeoisie family to question their current ideologies.

Pasolini said of the film “One part of the audience is scandalized. Scandal and hypocrisy are the same in all countries. One part of the audience laughs to defend itself. The other part of the audience admires it.”

The film won Pasolini the International Catholic Jury grand award at the Venice Film Festival but was simultaneously condemned by the Vatican for its content. The Italian government charged him with obscenity, and the charges were later dropped.

To close out the 1960s, Pasolini released the films Porcile,‘Pigsty’ and Medea

The new decade ushered in a new collection of films based on notable medieval literature. Il Decameron, ‘The Decameron’; I racconti di Canterbury, ‘The Canterbury Tales’; and Il fiore delle Mille e una Notte, ‘A Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights)’, make up the “Trilogy of Life".

Similar to his 1967 film Edipo re, ‘Oedipus Rex’, Pasolini used these works of literature because of the way they reflected modern times and themes. The films were humorous and risqué without causing too much alarm. This turned out to be a perfect combination as they were well received by the public and proved to be some of his most commercially successful films.

Pasolini’s final film came in 1975 with Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma, ‘Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom’. Competed only a few weeks before his death and released three weeks after, Salo is the pinnacle of the exploration into the psychology of the bourgeoisie. The film is based on Marquis de Sade’s eighteenth-century novel, Les 120 journées de Sodome ou l'école du libertinage. Pasolini changed the setting from a medieval castle in the early 1700s to the 1940s Fascist Republic of Salò

In Pasolini’s own words: "The transposition takes place in Salo during the Fascist republic in 1944-45. All De Sade's sex, his sadomasochism, has a clear and specific function: the effect of what power does to the human body. The reduction of the human body to a commodity. The cancellation of another person's personality. So it's not just a film about power, but what I would call the anarchy of power. Because nothing is more anarchical than power. Power does whatever it wants. And what power wants is completely arbitrary, or imposed by economic needs that escape common logic. But besides being about the anarchy of power, the film is also about the nonexistence of history. That is, history as seen by a Eurocentric culture- Western rationalism and empiricism on the one hand, Marxism on the other- which the film wants to show as nonexistent."

The film premiered at the Paris Film Festival but was banned a couple of months later. The censorship of Salo by various film boards and governments was a fitting end to an author and filmmaker that had fought with censorship his whole career. Many countries banned the film or prevented uncut releases of the film until the 1990s and 2000s. The British Board of Film Censors banned it, only allowing various censored versions until 2000 when they finally permitted an uncut release. In Australia, it was banned until 1993, then re-banned in 1997, and was finally permitted a DVD released in 2010. It was not banned in the United States, which was one of the only countries that had a theatrical release of the film.

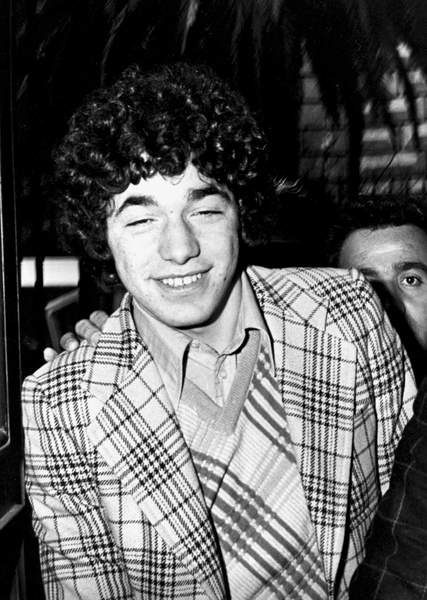

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s body was found on the morning of November 2, 1975, on a beach in Ostia, right outside of Rome. It is believed that he was beaten then run over with his own car. A teenager, Pino Pelosi, was arrested and pleaded guilty to the murder. In 2005, Pelosi confessed to not being the murderer and chose to stay silent for 30 years due to fear of putting his family in danger. Pelosi claimed there were five men that followed him and Pasolini until eventually striking, murdering him. In recent years it is thought that his death is connected with a book he was working on at the time of his death, titled Petrolio. Petrolio supposedly had new information surrounding the mysterious death of Enrico Mattei, an Italian public official. It is also theorized that his death was related to his political views or his homosexuality.

Pier Paolo Pasolini may be gone, but has most definitely not been forgotten. The Museum of Modern Art in New York ran retrospectives of his work in 1990 and 2012. British Film Institute had a retrospective in 2013. In 2014 Abel Ferrara released his film, Pasolini, which explores Pasolini’s final two days. Today, there is a literary garden in Ostia, Parco Pier Paolo Pasolini, in his memory.

Would you like to learn more about Pasolini's life through the reportages of important photographers represented by Bridgeman Images?

Pasolini by Mario Dondero

Pasolini by Federico Garolla

Pasolini by Sandro Becchetti

Pasolini by Farabola